On April 2, 1792 Congress passed the Coinage Act, establishing the first national mint in the United States. During the Colonial Period, monetary transactions were handled using foreign or colonial currency, livestock, or produce. After the Revolutionary War, the U.S. was governed by the Articles of Confederation, which authorized states to mint their own coins. In 1788, the Constitution was ratified by a majority of states and discussions soon began about the need for a national mint.

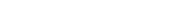

Congress chose Philadelphia, what was then the nation’s capital, as the site of our first Mint. President George Washington appointed a leading scientist, David Rittenhouse, as the first director. Rittenhouse bought two lots at 7th and Arch Streets to build a three-story facility, the tallest building in Philadelphia at the time. It was the first federal building erected under the Constitution.

Coin production began immediately. The Act specified the following coinage denominations:

In copper: half cent and cent

In silver: half dime, dime, quarter, half dollar, and dollar

In gold: quarter eagle ($2.50), half eagle ($5), and eagle ($10)

In March 1793, the Mint delivered its first circulating coins: 11,178 copper cents.

In 1795, the Mint became the first federal agency to employ women: Sarah Waldrake and Rachael Summers were hired as adjusters. Learn about their contribution to the Mint’s history and about other trailblazing women at Women at Work.

Southern Branch Mints

In the early 1800s, America experienced its first two gold rushes: first in North Carolina and then in Georgia. Demand on the Philadelphia Mint to melt, refine, and produce coins from this gold pushed the Mint to its limits. In 1835, Congress passed legislation to establish three new branch Mints located in Charlotte, NC; Dahlonega, GA; and New Orleans, LA. Charlotte and Dahlonega concentrated on processing the miners’ gold into coins, while New Orleans minted both gold and silver coins to keep up with a growing America.

In 1861 at the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy gained control of these three facilities, sporadically making Confederate coinage before converting all of them to assay offices. The U.S. regained possession of the facilities in 1862. Dahlonega never reopened, and Charlotte opened briefly in the 1870s as an assay office. The New Orleans Mint opened in 1879 to produce silver and gold coins until it stopped coining operations in 1909.

Mint Expands West

In 1849, the California Gold Rush brought a flood of people west for the chance to get rich. Transporting the gold east all the way to the Philadelphia Mint was time-consuming and risky. In 1854, a branch Mint opened in San Francisco to convert the miners’ gold into coins. By the end of that year, the San Francisco Mint produced $4,084,207 in gold coins.

Gold fever spread to Colorado in 1858, bringing hundreds of people to settle around the new city of Denver. In 1862, Congress approved a branch Mint in Denver and bought the building of Clark, Gruber and Company, a private mint. The following year, the Denver facility opened as an assay office for miners to bring gold to be melted, assayed, and cast into bars. It didn’t produce any gold coins, as was originally intended. In 1895, Congress converted the Denver facility back to a Mint, and in 1906 it produced its first gold and silver coins.

In 1864, in response to Oregon’s own gold rush, Congress authorized a branch Mint in Dalles City, Oregon and constructed a building. However, no minting or assaying duties were ever performed. Congress gave the building to the state in 1875 to use for educational purposes.

The country’s largest silver strike, referred to as the Comstock Lode, started in Nevada in 1859. Congress authorized a branch Mint in nearby Carson City. The Carson City Mint opened in 1870 to accept deposits from the Comstock Lode and to mint coins. During its operation, it produced eight different coin denominations. Congress withdrew its mint status in 1899 when the Comstock’s ore declined, but it continued as an assay office until 1933.

Assay Offices

Gold and silver pouring in from strikes throughout the West created the need for assay offices around the country to assess and process the metal ore. Most closed in the early 1900s when the metal deposits waned. The New York Assay Office in Manhattan was the notable exception; it stayed in operation for almost 130 years, finally closing in 1982. Explore the assay offices and their years of operation in the table below.

| New York Assay Office (NY) | 1854-1982 |

| Boise Assay Office (ID) | 1872-1933 |

| Helena Assay Office (MT) | 1877-1933 |

| St. Louis Assay Office (MO) | 1881-1911 |

| Deadwood Assay Office (SD) | 1898-1927 |

| Seattle Assay Office (WA) | 1898-1955 |

| Salt Lake City Assay Office (UT) | 1909-1933 |

Bullion Depositories

The Mint’s demand for the gold and silver needed to produce coins in increasing quantity for the growing U.S. population meant that there needed to be a secure location to store the country’s bullion. In 1936, the Fort Knox Bullion Depository opened in Kentucky. The next year, the facility received its first shipment of gold from the Philadelphia Mint and New York Assay Office. The bullion was shipped by train through the U.S. mail.

In 1938, the West Point Bullion Depository opened to store silver bullion. It remained a storage facility until 1973 when it started producing pennies to reduce the production pressure on the Mint facilities. It also produced Bicentennial quarters in 1976, and gold medals starting in 1980. It gained official status as a Mint in 1988.

Today, the Mint maintains production facilities in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Denver, and West Point, and a bullion depository in Fort Knox.