Women have been an essential part of the U.S. Mint’s story from the beginning. Just three years after the Coinage Act of 1792, the Mint hired its first two female employees. In the years that followed, women gained opportunities not readily available to them in other industries at the time. Starting in the role of adjuster, they spread into clerkships, coin press operators, managers, to all sections of the Mint workforce.

The Mint hired Sarah Waldrake and Rachael Summers in 1795 to work as adjusters. We don’t know much about the women, or the circumstances that led to their hiring. But from historic accounts, we do know about their duties and work conditions.

Coin production was a very labor-intensive process in the 1790s and early 1800s. Some machines, like the heavy rollers used to flatten ingots into long strips, were powered by horses. Others, like those used to punch out blank coins and to strike the coins, were powered by men. But there was one position that the Mint felt was ideally suited to women: the role of adjuster. Adjusters weighed blank coins and “adjusted” those weighing too much by filing them down.

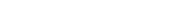

The number of adjusters at the Philadelphia Mint started off small at six, but as coin production increased and the need for more adjusters grew, the Mint hired more people to fill the role. Based on historic accounts, this role became the exclusive domain of women by the mid-1800s. Descriptions of the San Francisco and Philadelphia Adjusting Rooms in 1856 and 1861 noted that all adjusters were women.

Life as an Adjuster

In the Adjusting Room, adjusters sat at long tables and each had an assay scale and a file. The women often wore short sleeves to minimize brushing metal dust onto the floor, and a leather apron attached to the table to catch any metal that did fall. They socialized as they worked, since the Adjusting Room was separated from the noise involved in the rest of the coin production process.

The Adjusting Room was poorly ventilated, with all doors and windows tightly shut, as any air current affected the accuracy of the scales. Because this made for very uncomfortable work conditions, the women took breaks throughout the day to open windows. In comparison to the textile mills and other factories that were the dominant employers of women in the 19th century, the Mint supplied a relatively safe and social place for women to work.

Expanding Roles for Women

In the 1830s, the steam engine replaced man and horse power to run the Mint’s machines. Steam power opened more positions to women due to the decreased effort needed to produce coins. Adjusters were still an important part of the production process, but by the 1860s women also operated the improved milling machines and coin presses. Both machines required the operator to simply drop blank coins into tubes that fed into the machines. The milling machine created a raised rim around the blanks before the coin presses struck the designs.

At the same time, women also moved into the administrative offices of the Mint. In 1865, Elizabeth Wyer became the first woman clerk; she worked in the Superintendent’s Office of the San Francisco Mint. Other women gained similar opportunities at other Mint branches.

Up until 1877, men supervised women. But that year, Elvira Cowan became the first woman to receive a supervisory position, managing the adjusters at the Carson City Mint. Other women soon followed, supervising adjusters in other Mint facilities as well as managing clerks in the administrative offices.

By 1911, a woman filled the second highest position at the Mint. At this time, women still did not even have the right to vote (that came in 1920). Margaret Kelly held the title of examiner, although newspapers referred to her as the “assistant director,” a title not created until 1924 and filled by Mary O’Reilly.

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Nellie Tayloe Ross as the first female director of the Mint. She also served the longest term: 20 years. Following her were Eva Adams (1961–1969), Mary Brooks (1969–1977), Stella Hackel Sims (1977–1981), Donna Pope (1981–1991), and Henrietta Holsman Fore (2001–2005). For more information about these women and their contributions to the Mint, read “Six Women Who Have Led the Mint.”

Today, women still make history at the Mint. Women work in crucial positions such as chemists, medallic artists, metal forming machine operators, lawyers, and executives. None of this would have been possible without Sarah Waldrake and Rachael Summers paving the way for those who came after.